Essays from a broad range of perspectives on bar admissions-related topics, with the goal of stimulating conversation and promoting understanding among the different stakeholders in bar admissions.

This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, Spring 2021 (Vol. 90, No. 1), pp. 63–68. Roy M. SobelsonI have long been interested in how law schools should address student lack of candor on character and fitness questions about records or behavior that may prevent them from being admitted to the bar.

During my service as Georgia State University (GSU) College of Law’s Assistant Dean for Student Affairs, my subsequent 11-year service as GSU’s Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, and my membership in the State Bar of Georgia and service on several of its committees, I was able to appreciate the issue from the perspectives of law students, law schools, and bar admission personnel, all quite different from one another. Each of my roles taught me something new and influenced my understanding of this topic.

Conduct Prior to Law School: How Will That Affect My Bar Admission Prospects?

I was GSU College of Law’s first Dean for Student Affairs, a position created for students to have a familiar face to turn to when they have issues that interfere with their educational success, from housing or financial aid to personal problems like depression, low self-esteem, or struggles with alcohol and other drugs. Issues arising from their conduct preceding law school were barely among the things I initially thought about, but I soon came across students concerned about bar admission problems arising from conduct prior to law school.

Most typically, the concerns arose from arrests or convictions, drug abuse, or treatment for mental health conditions. The more serious the conduct, the more likely the student intentionally omitted or misrepresented it on their law school application. And the numbers were much greater than I would ever have guessed. Even as to less serious misconduct, most especially driving and alcohol-related offenses, several students picked and chose what to reveal on their applications. Their reasons for doing so included, “I didn’t think I’d get in if I told you,” “I didn’t read the question closely,” “I’m not that person anymore,” and (my all-time favorite) “My mother filed my application for me.” It seemed clear to me that many applicants did not take the application process as seriously as they should have.

Disclosure Discrepancies: An Honor Code Violation?

When I became Associate Dean of Academic Affairs, I was charged with supervising the law school’s Honor Code. In that capacity, I became the person to whom students, faculty, and staff reported when concerns arose about a student’s inappropriate behavior. Because our law school’s Honor Code covered both academic and non-academic infractions, I became privy to a wide range of concerns.

I became acutely aware of an ambiguity of the Honor Code process on the question of whether a prospective student’s misrepresentation on their law school application could be prosecuted under our Honor Code. Inasmuch as we usually first became aware of a student’s misrepresentation when they were well into their law school career (usually because they had eventually told bar admission authorities something they had not told us), this issue became the subject of intense debates among administrators and faculty members surrounding the prospect of imposing on a known student (particularly one who had a stellar law school record) severe consequences, such as suspension or even expulsion, just short of graduation.

Due to our school’s culture and my engagement with students on a personal level, I began to see a steady uptick in the number of students seeking my advice and aid handling issues related to their bar admission. At times, I experienced severe cognitive dissonance, knowing that I was simultaneously managing the Honor Code and being asked for personal advice on matters that might implicate the Code. In most instances, I’m happy to say, the students’ concerns were exaggerated. Even so, I thought that asking too many questions was always better than asking too few, and I slowly but surely became a point person for seeking information about all manner of questions relating to bar admissions.

But I Was Told I Didn’t Need to Disclose This …

In the course of my discussions with students, I learned that very few practicing lawyers have a real understanding of the bar admissions process, which has led many of them to give students some terrible advice. I was also surprised at how common this was among some judges, who often advised college or law students at sentencing (most often for DUIs or misdemeanors like shoplifting) that they didn’t need to reveal certain information to law schools or bar admission authorities, or both.

I can think of at least a half dozen occasions when I had to confront students about misrepresentations on their law school applications, which we had come to learn about because the bar admission office had discovered inconsistencies between their bar admission and law school applications. When I asked the students to explain the inconsistencies, they often said that a lawyer (or even a judge who’d heard their case) had told them that they weren’t obligated to reveal the information to the law school. When I asked the students whether the lawyer or judge had actually read the law school application questions before telling them this, not once did a student answer “Yes.” In fact, virtually all of them reacted as if it had never occurred to them to think about that.

I also saw that students could occasionally be their own worst enemies when they were not appropriately and timely advised about the best way to deal with some of these disclosure issues. Unfortunately, denial and delay were often the preferred methods of coping. Neither serves the student well.

A Law School’s Responsibility: Simply to Educate or Beyond?

My third source of education on these matters came from my long-standing membership in the Georgia bar. I served on several bar committees, including those related to professionalism, not to mention committees on which I served in my capacity as an Associate Dean of one of Georgia’s five law schools.

In the course of serving on committees, I discovered that some law schools and their administrators had radically different views from mine about schools’ responsibilities to the profession when it came to students whose behavior might create barriers to admission. In particular, some schools took the position that their job was solely to educate students, not to judge them or to act as gatekeepers, and this occasionally led them to take actions I considered to be inappropriate, such as ignoring, sanitizing, or excusing students’ Honor Code infractions.

Eventually, I decided I had to take some steps to make GSU’s position on this matter clear (both within the school and beyond) and to allow us not only to properly advise our students about the best ways to behave, but also to deal with those rare situations in which a student’s behavior is worthy of condemnation or other consequences.

GSU’s Three-Step Approach to Better Prepare Students for the Bar Admissions Process

Step 1: Communication

First and foremost was to repeatedly talk to faculty and students about the bar admissions process, from the first day of law school orientation until graduation. Frankly, I’d always been a bit surprised by how incurious students were about many aspects of the legal profession, including the hurdles they had to clear to join it. We eventually expanded the scope of this emphasis by broaching the subject of bar admissions in open house events we held for prospective students, to make it clear how seriously we took the matter.

Step 2: Aligning the Law School Application Questions with Those on the Bar Admission Application

Second, I revised the law school’s application materials to better align the questions asked on the application with those asked at the bar admissions stage. I compared applications from several selective schools and realized that there was a great deal of variety, which made it difficult for students to decide whether information they gave to one school should be the same as what they gave to other schools.

I spoke with the local bar admission authorities every year and changed our application questions to match those asked on the bar admission application. In fact, in some instances, our discussions led to modifications of both their questions and ours. That eventually eliminated the issues that arose when the answers given “inconsistently” between the law school and bar admission applications could be explained away or excused by differences in the questions.

Step 3: Declaration of Disclosure Form

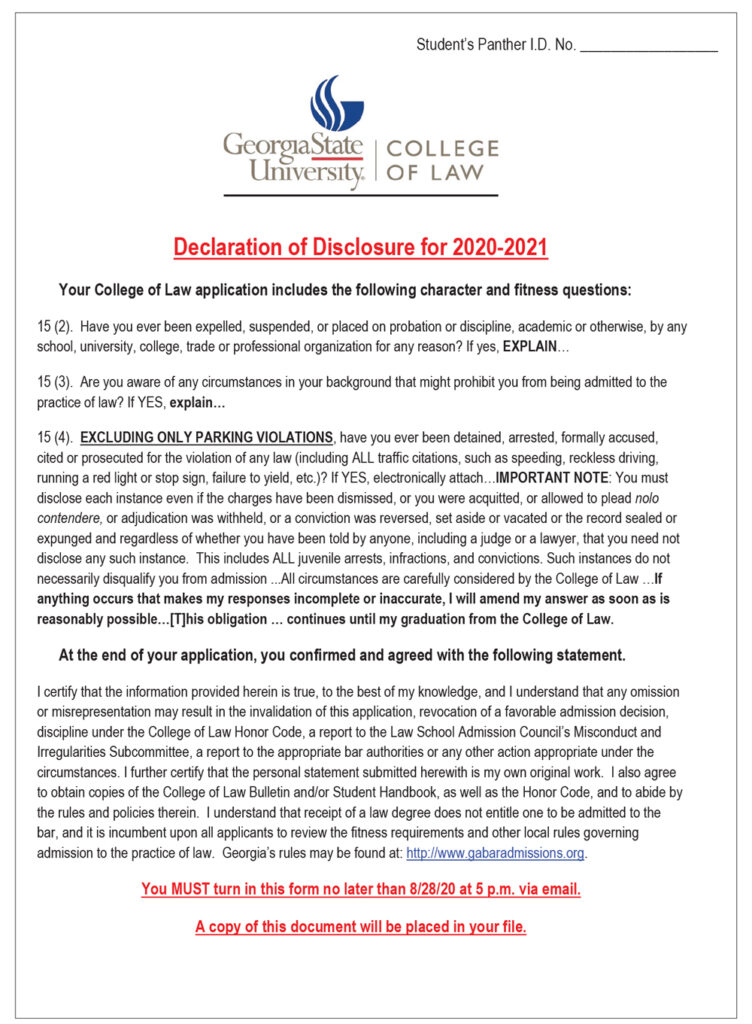

My final step, which arose from a listserv posting from a fellow associate dean about these issues, involved creating a Declaration of Disclosure form (see below), which GSU has used at first-year orientation sessions since the form’s creation about 10 years ago. (Unfortunately, I don’t remember who the associate dean was, so I’ve never been able to properly thank and credit them.) It is actually very simple, but it has made a world of difference in dealing with some of these issues.

The first page of the form lists the questions students were asked on their law school application about a number of character issues, then repeats the admonition from the application that giving false information can have serious consequences, both in law school (such as Honor Code prosecutions) and after law school (in the bar admissions process).

On the second page, students are asked to check one of two boxes to either (1) confirm that all they disclosed on their application was complete and accurate or (2) seek permission to amend, providing details and an explanation for any omissions or misrepresentations.

The form makes it clear that the process is discretionary, and that even if the student is allowed to amend, that does not necessarily mean that there will not be consequences for any omission or misrepresentation. Finally, the form reminds them that their obligation to report certain conduct to us continues until they graduate.

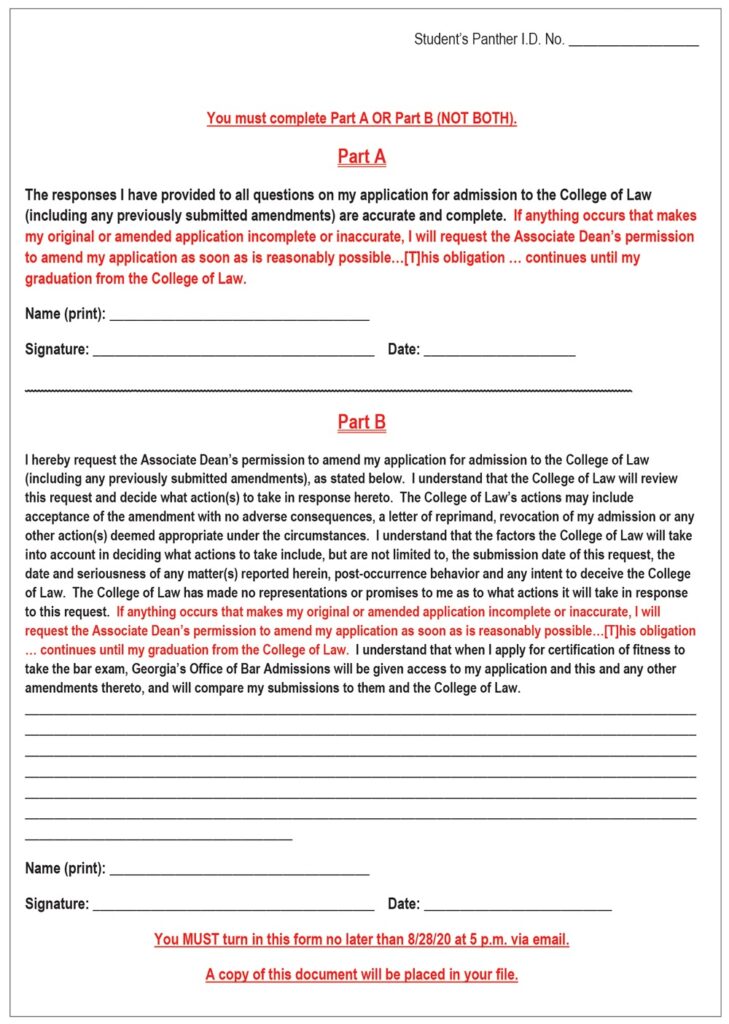

As important as the form is, I regard the ceremony at which the students complete it as essential. This ceremony is part of an entire afternoon orientation session devoted to professionalism. While the students are initially provided with a sample copy of the form in their materials before orientation, they are told to not yet complete it. Completion takes place during the same ceremony at which they receive an ethics lecture from a distinguished lawyer or judge, an introduction to the bar admissions process by an official from the admission office, and the administration of an Honor Code pledge to the entire entering class. During this ceremony, we distribute a clean form to each student, read it aloud, and field questions before asking them to fill it out and turn it in.

The rest of the afternoon’s orientation involves discussion groups in which students discuss a series of ethics and professionalism hypotheticals. Each group includes about a dozen students and two discussion group leaders. A few faculty members serve as group leaders, but the vast majority of the leaders are local lawyers or judges. The nature of the hypotheticals (some about law school, some about the practice of law), not to mention the very existence of the program, is intended to further emphasize to students just how important a role ethics and professionalism will play in their lives. The use of volunteer discussion leaders is also quite intentional, the purpose being to introduce students to the importance of public service in their careers.

Students seeking permission to amend are sometimes asked to meet with the associate dean. Some meetings are intended simply to emphasize the importance of the disclosure process, and maybe to tell a student how close they came to making a critical mistake. On a few occasions, we have denied students the right to amend, and even revoked a couple of law school admission decisions. The form and a description of any meetings or other actions taken are noted in every student’s permanent file.

Benefits Derived from GSU’s Three-Step Approach

It is impossible to quantify with any certainty just what impact these steps have had, but five distinct differences were noticeable after we adopted these procedures.

Faculty members became more invested in raising disclosure issues with students and encouraged anyone with questions or concerns to consult with me or them.

Administrators from all five Georgia law schools not only engaged in further discussions on these issues, but they all eventually adopted their own versions of the Declaration of Disclosure form and the ceremony at which it is completed.

The connection between the law school administrators and the bar admission authorities was strengthened on a host of issues, all to the benefit of the students, the schools, and the bar.

Students are now more aware than ever before of the need to be honest and precise from the beginning of their careers, knowing that making a bad decision could eventually undermine everything they work so hard to achieve before and during their law school careers. I’d like to think those same lessons carry on far beyond law school and bar admission, as well.

Any student who makes the unfortunate choice to hide information well into their law school career (or even after admission) will not be able to claim that they didn’t know just what the right course of action was.

Using the Declaration of Disclosure form is simple and efficient, and the accompanying ceremony enhances its effectiveness, providing students with a memorable and thought-provoking experience.

Used in isolation, however, the form could easily become just another piece of paper in a file. In order for this all to work, law school administrators need to sell the concept to faculty members and students, so that all are on board and everyone gives students the appropriate advice and direction. Schools also need to talk about the importance of these issues with students from the first time they meet prospective students to the day those students graduate.

Communication Between Law Schools and Bar Admission Authorities Is Key

There’s one more piece to this puzzle. I have always been lucky enough to have good personal relationships with our state’s director of bar admissions, the members of the Supreme Court to whom they report, and the president and other officials of the State Bar. And whenever I have called upon any of them to visit classes, attend law school events, speak at graduation, or support us in any significant way, they have stepped up. Those relationships have made it easy for me to raise issues with them on this subject, and I hope that they have felt the same about raising issues with me or other associate deans.

But even with very good relationships, there is one element that, in my experience, needs attention from both the law schools and the bar admission authorities. It is that the bar admissions process—more specifically, the character and fitness screening process, and the interviews conducted with some applicants—is, to law schools and students, somewhat of a “black box.” This means that any discussions I had with students about potential interviews were necessarily limited to what little I could glean from speaking to the few students who were willing to discuss their experiences, after the fact. Knowing more about the interview process would have helped me better prepare students for the process ahead and convey to them the significance of proper and timely disclosure.

Law schools must continue to work to create relationships of trust and respect with the bar admission offices, and vice versa. Better communication between law schools and bar admission personnel, being transparent about what each is doing, and impressing upon students and the public the importance and integrity of their work are key to helping law schools serve their students and will ultimately serve the public and the bar.

Roy M. Sobelson served as the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at Georgia State University College of Law from 2006 to 2016, and as the college’s first Associate Dean for Student Affairs from 2003 to 2005. Prior to that, he taught Professional Responsibility, Civil Procedure, and Evidence at GSU from 1985 to 2018.

Roy M. Sobelson served as the Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at Georgia State University College of Law from 2006 to 2016, and as the college’s first Associate Dean for Student Affairs from 2003 to 2005. Prior to that, he taught Professional Responsibility, Civil Procedure, and Evidence at GSU from 1985 to 2018.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.